AbstractSparganosis is a parasitic infection caused by the plerocercoid tapeworm larva of the genus Spirometra. Although the destination of the larva is often a tissue or muscle in the chest, abdominal wall, extremities, eyes, brain, urinary tract, spinal canal, and scrotum, intramuscular sparganosis is uncommon and therefore is difficult to distinguish from a soft tissue tumor. We report a case of intramuscular sparganosis involving the gastrocnemius muscle in an elderly patient who was diagnosed using ultrasonography and MRI and treated by surgical excision. At approximately 1 cm near the schwannoma at the right distal sciatic nerve, several spargana worms were detected and removed.

INTRODUCTIONSparganosis is a rare parasitic infection caused by a migrating plerocercoid tapeworm larva (=sparganum) of the genus Spirometra [1]. The sparganum is a wrinkled, whitish, ribbon-shaped organism that is a few millimeters wide and up to several centimeters long. Sparganosis is transmitted to humans by drinking water contaminated with copepods containing spargana, consuming the raw flesh of a second intermediate host such as frogs or snakes, or placing a poultice infected with spargana on an open wound [2,3]. Although sparganosis may involve internal organs, such as the eyes, brain, and spinal cord, the clinical presentation of sparganosis usually occurs after the larvae have migrated to a subcutaneous location. Furthermore, because the mass is usually non-tender in early migratory stages and sometimes triggers a painful inflammatory reaction in the surrounding tissues, it is quite difficult to differentiate sparganosis from a soft tissue tumor based on preoperative radiographic and laboratory data [4]. In addition, intramuscular sparganosis in the lower extremities has been very rare. We report here a rare case of intramuscular sparganosis involving the gastrocnemius muscle in an elderly patient who was diagnosed by ultrasonography and MRI and treated by performing surgical excision.

CASE REPORTA 77-year-old man was referred to our clinic from a private clinic because of a suspected soft tissue tumor. The patient had a 6-month history of a mass over the right posteromedial aspect of the proximal tibia. Physical examination revealed a 3 cm×1 cm, soft, non-tender mass at the posteromedial aspect of the right proximal tibia, and the mass was freely mobile and easily compressed. Another mass was found at the posterior aspect of the right proximal tibia. He had pulmonary tuberculosis when he was 30 years old, for which he was treated and believed to have been cured. He also had the history of lobectomy because of a lung cancer in the left lower lobe at the age of 47 years and received a total gastrectomy due to an advanced gastric cancer at the age of 71 years.

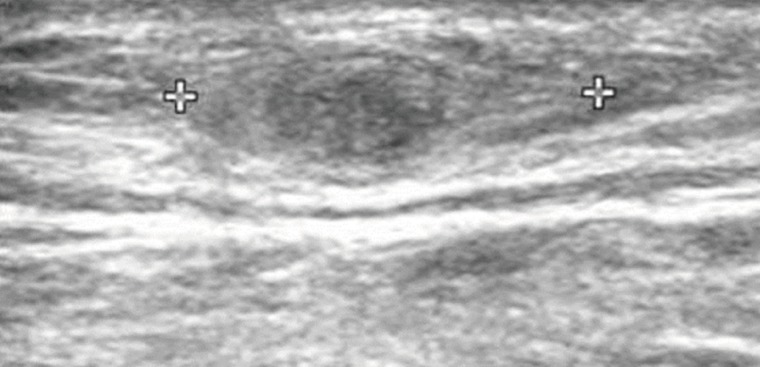

Routine laboratory test results were unremarkable, and no eosinophilia was noted. Plain radiographs of the right leg revealed multiple calcifications extending from the medial part of the knee to the calf. Ultrasonography revealed a heterogeneous, hyperechoic mass with a hypoechoic tubular lesion in the gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 1), and MRI revealed multiple tubular and cystic lesions in the gastrocnemius muscle. The lesions showed high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and multilobulated, peripheral enhancing low signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Fig. 2). The patient was a farmer, and he had occasionally ingested raw snake meat when he was young. Preoperative serodiagnosis of human sparganosis by using a monoclonal antibody-based competitive ELISA was positive (3.79 in OD value) (negative < 1.00).

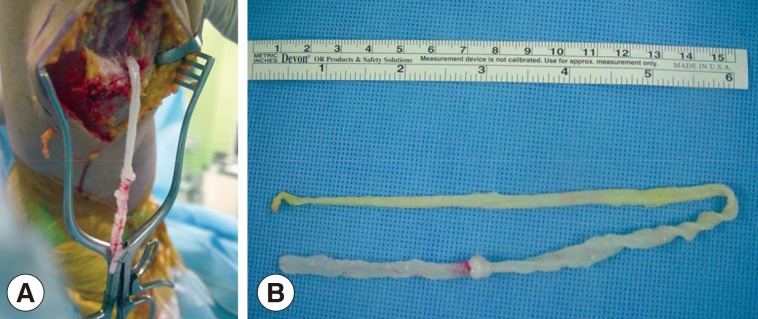

After preoperative ultrasound-guided marking for suspected cystic lesions, a longitudinal incision was made on the posterior aspect of the proximal tibia. A white, shiny, synovium-like piece of tissue emerged from the incision, and this was identified as a sparganum that measured 30 cm in length and 0.5 cm in width and was wriggling after removal from the patient (Fig. 3). The calcified foci near the calf were also removed, and these tracts possibly represented the pathway along which the larvae had passed.

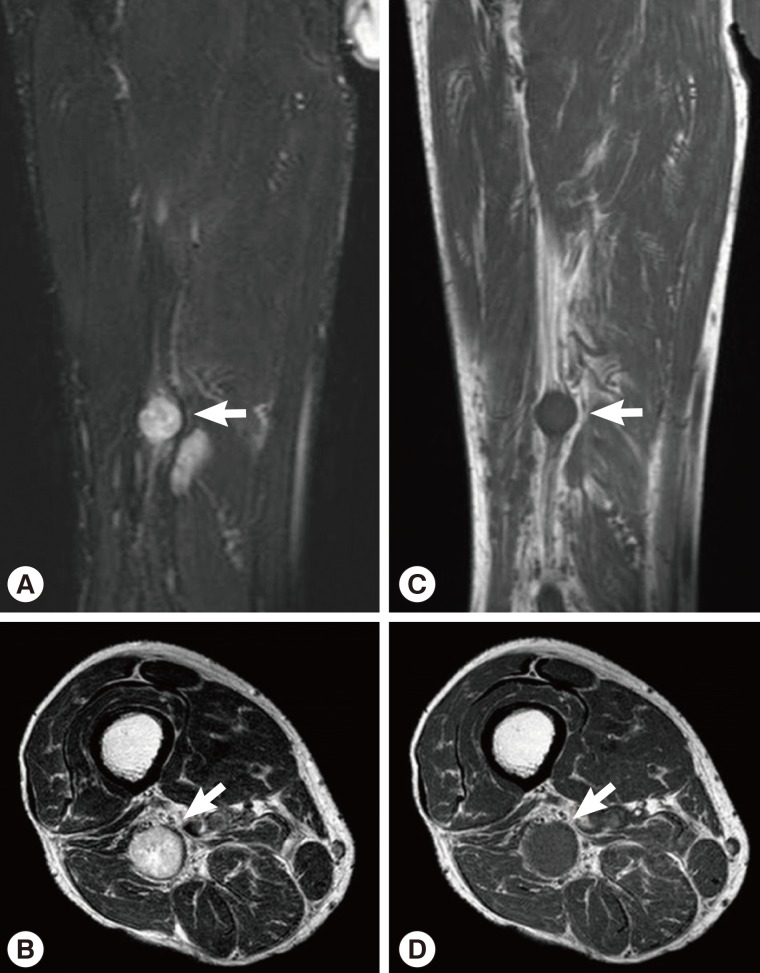

Sixteen months after the operation, the patient revisited our hospital because of pain and paresthesia of the right thigh and a mass at the posterior aspect of the right distal thigh. Physical examination revealed generalized pain and a tingling sensation on the right thigh and multiple soft, mobile, non-tender masses at the posterior aspect of the right proximal tibia. MRI revealed a 1.8 cm-sized, well-circumscribed round mass arising at the right distal sciatic nerve. The lesion showed heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images with a target sign or a fascicular sign, and a benign neurogenic tumor, such as a schwannoma or neurofibroma, was suspected (Fig. 4). Multifocal tubular and cystic lesions were also detected around the mass, showing high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and low signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Fig. 5).

An excisional biopsy was performed, and a histologic analysis revealed a schwannoma showing spindle tumor cells in a palisading pattern (Fig. 6). In the operative field, approximately 1 cm near the mass, several spargana worms were detected and removed at the same time.

DISCUSSIONIntramuscular sparganosis is extremely rare. Cho et al. [5] reported that 54 of 70 cases of sparganosis in Korea were found in the subcutaneous tissue or intermuscular fascia, 7 cases in the body cavity, 6 cases in the orbit, 2 cases in the urinary tract, and 1 case in the submucosal tissue, but no cases occurred in muscles. However, Kim et al. [6] reported a case of intramuscular sparganosis in the sartorius muscle in 2001, and Kim et al. [7] reported a case of living sparganosis in the forearm flexor muscle in 2001. Recently, Lee et al. [8] reported a case of living sparganum for 20 years migrating from the knee joint to the ankle joint along the calcified tract in 2010. Ha et al. [9] also reported a case of sparganosis combined with bursitis involving the medial gastrocnemius muscle of the proximal lower extremity in 2011. Here we report a case of intramuscular sparganosis involving the gastrocnemius muscle in a 77-year-old man.

The clinical manifestations of sparganosis are diverse, such as palpable masses, non-specific discomfort, vague pain, headache, or even no symptoms, depending on the organs involved. The most frequent finding is a subcutaneous nodule resembling a soft tissue tumor. Thus, it is quite difficult to differentiate sparganosis from a soft tissue tumor based on the clinical manifestation and preoperative radiographic findings.

Currently, sparganosis can be diagnosed based on serology like ELISA. Sparganosis patients can often show eosinophilia [10]. Although the precise function of eosinophils is unclear, they are anyway involved in destroying the parasitic organisms [11]. A competitive ELISA that uses sparganum-specific monoclonal antibodies has been developed to improve the diagnostic specificity of sparganosis [12]. Even though our patient did not show definite eosinophilia, a monoclonal antibody-based competitive ELISA was positive. Radiologic evaluation, such as plain radiography, ultrasonography, or MRI, is also useful for the diagnosis of sparganosis. In our patient, preoperative ultrasonographic findings showed a heterogeneous, hyperechoic mass with a hypoechoic tubular lesion in the gastrocnemius muscle. This heterogeneous, hyperechoic mass is considered to be a granuloma that contains the living sparganum, and the internal hypoechoic tubular lesion is considered to be the empty migrating tract of the larva. Multiple calcifications seen on plain radiographs can also be considered the pathway along which the sparganum passed. In this case, we performed preoperative ultrasound-guided marking for suspected lesions. Therefore, we could easily find intramuscular sparganum during the surgery, although it is difficult to determine the location of the spargana with naked eyes in the operative field.

Human sparganosis is a surgical disease because the diagnosis depends almost entirely on detecting larvae from the lesions. Thus, in areas where sparganosis is endemic, the presumptive diagnosis can be made preoperatively by an experienced surgeon if the patient has a history of eating raw meat, together with the size, migration, and crepitation of the mass. However, it is quite difficult to differentiate sparganosis from a soft tissue tumor based solely on the clinical manifestations and preoperative radiographic findings. Furthermore, because the incidence of this disease is extremely low, even in endemic areas, it is difficult for surgeons to suspect sparganosis based only on the preoperative data. Thus, an immunodiagnosis for sparganosis is recommended when soft tissue tumors are detected in patients living in endemic areas [6]. In addition, sparganosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of soft tissue tumors, especially among patients who frequently consume mountain water or raw snake or frog meat.

In our case, although definite eosinophilia was not detected, we could suspect intramuscular sparganosis involving the gastrocnemius muscle based on the patient's habit of ingesting raw snake meat during his adolescence, multiple calcifications on plain radiography, a heterogeneous, hyperechoic mass with a hypoechoic tubular lesion on ultrasonography, multiple tubular and cystic lesions in the gastrocnemius muscle on MRI, and the positive ELISA using sparganum-specific monoclonal antibodies. In addition, we could easily remove the intramuscular sparganum with the aid of preoperative ultrasound-guided marking for suspected lesions.

In our case, the patient revisited our hospital because of pain and paresthesia of the right thigh, and in the operative field, approximately 1 cm near the schwannoma at the right distal sciatic nerve, several sparganum were detected and removed. Schwannomas are tumors arising from the Schwann cells of the neural sheaths of the motor and sensory nerves, and if schwannomas occur in the lower limb, they are found in association with either the sciatic nerve (1%) or the posterior tibial nerve. All ages and both sexes may be affected, but schwannomas are most frequently seen in patients between 40 and 50 years of age. Benign schwannomas are generally slow-growing tumors arising from the Schwann cells of the peripheral nerve sheath, so patients with a sciatic schwannoma are usually asymptomatic until a local mass compresses the sciatic nerve. These masses are more often associated with the sensory aspect of the nerve; thus, surgical excision is the treatment of choice in symptomatic sciatic schwannomas. Although the etiology of these benign neurogenic tumors is unknown, in our patient, we considered that intramuscular sparganum might irritate the neighboring sciatic nerve, and we removed all the adjacent spargana worms.

REFERENCES1. John DT, Petri WA. Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology. 9th ed. St Louis, Missouri, USA. Saunders, Elsevier. 2006.

2. Chang KH, Cho SY, Chi JG, Kim WS, Han MC, Kim CW, Myung H, Choi KS. Cerebral sparganosis: CT characteristics. Radiology 1987;165:505-510. PMID: 3659374.

4. Kwon SY, Rhee SK, Lee HS, Kim KW, Chae Y. Sparganosis in subcutaneous tissue of thigh: case report. J Korean Orthop Assoc 1998;33:207-210.

5. Cho SY, Bae JH, Seo BS. Some aspects of human sparganosis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol 1975;13:60-77.

6. Kim JR, Lee JM. A case of intramuscular sparganosis in the Sartorius muscle. J Korean Med Sci 2001;16:378-380. PMID: 11410706.

7. Kim BH, Nam U, Choi MH. Living sparganosis in the forearm flexor muscle. J Korean Orthop Assoc 2001;36:489-491.

8. Lee JK, Myung NH, Park HW. A case of sparganosis in the leg. Korean J Parasitol 2010;48:309-312. PMID: 21234233.

9. Ha KY, Oh IS. Case report: Lower extremity sparganosis in a bursa. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469:2072-2074. PMID: 21519938.

10. Hong D, Xie H, Zhu M, Wan H, Xu R, Wu Y. Cerebral sparganosis in mainland Chinese patients. J Chin Neurosci 2013;(in press).

12. Yeo IS, Young TS, Im K. Serodiagnosis of human sparganosis by a monoclonal antibody-based competition ELISA. Yonsei Med J 1994;35:43-48. PMID: 8009896.

Fig. 1Ultrasonography of the patient which revealed a heterogeneous, hyperechoic mass with a hypoechoic tubular lesion (crosses) in the gastrocnemius muscle.

Fig. 2MRI showing multiple tubular and cystic lesions of high signal intensity on coronal and axial T2-weighted images (arrows) (A, B) and multilobulated, peripheral enhancing low signal intensity on coronal and axial T1-weighted images (arrows) (C, D) in the gastrocnemius muscle.

Fig. 3Intraoperative photographs showing a sparganum in the right proximal lower extremity (A) and the removed sparganum with a wrinkled, whitish, elongated ribbon-like shape (B).

Fig. 4MRI showing a 1.8 cm-sized, well-circumscribed, round mass arising at the right distal sciatic nerve. The lesion showed heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (arrows) (A, B) and intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images (arrows) (C, D) with a target sign or a fascicular sign.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||